Some prominent economists are concerned that the U.S. is entering an era of permanently higher inflation, but Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell believe the current spike will be temporary. So far, this debate has largely been missing three dimensions: what the best forecasters are saying, what’s happening in other countries, and steps that can be taken to attenuate problems in the supply chain.

The inflation debate is familiar to anyone following financial markets or the policy discussion in Washington. The policy response has been massive — fiscal measures amounting to 22 per cent of GDP have been enacted, not even counting direct support for the health-care sector. This has led to concerns that the government is “overfilling the bathtub” and creating higher inflation that, once it takes root, will be hard to eradicate.

At the same time, some inflation is to be expected as the economy re-opens and many of the hardest-hit sectors, from hotels to airlines, see their customers return. A variety of supply-side chokeholds, from semiconductor-chip shortages to container-shipping delays, are also putting upward pressure on prices.

The hard question is whether higher inflation, such as we saw in April, is a blip (as Janet Yellen suggests) or a harbinger of a longer-term problem (as economist Larry Summers contends). The best forecasters are definitively on Yellen’s side. And they include not only the people responsible for the leading macro-econometric models at the Federal Reserve, the Council of Economic Advisers and Wall Street banks (1)

They also include “superforecasters” participating in the Good Judgment Project associated with Philip Tetlock at the University of Pennsylvania, who have outperformed analysts in many fields, including intelligence analysts with access to classified information. These experts tend to be “foxes” rather than “hedgehogs,” collecting small pieces of new data and updating their previous views rather than sticking to one dogmatic perspective. And they are mostly dismissive of the Summers view.

For example, the superforecasters do see a notable pickup in inflation this year, assigning a 42 per cent chance that it will exceed three per cent in 2021 (2). But 2022 is a different story. They assign only a seven per cent chance that inflation will be that high next year — so in effect they think Yellen has a 93 per cent chance of being right. To reinforce the point, they predict a 44 per cent chance of inflation being below two per cent next year. And these forecasts haven’t moved much despite all the recent press and market hoopla: In mid-March, the superforecasters saw a five per cent chance of the high-inflation scenario for next year.

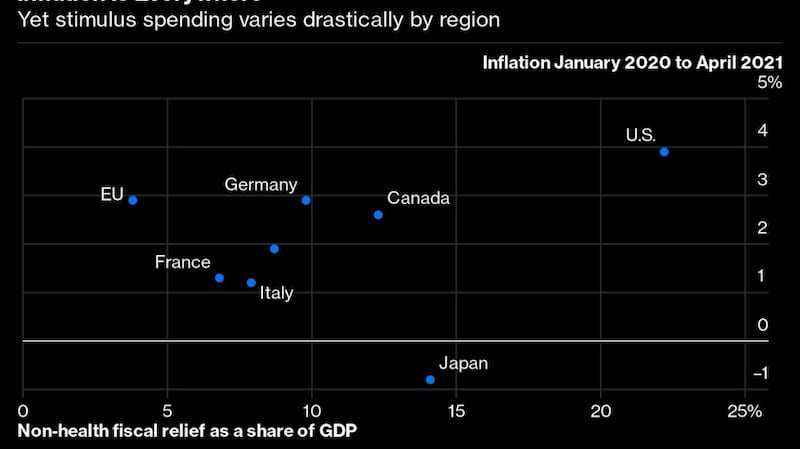

The evidence from other countries provides further perspective on whether America’s disproportionately strong fiscal response is the main driver of current inflation, which in turn could indicate whether it will become permanent. Inflation has been rising in G-7 countries and in the Euro area, and most of this increase seems unrelated to the countries’ drastically different fiscal responses. The scatterplot below shows that the U.S. is a large outlier on the size of its fiscal relief, but only a modest outlier on inflation (3). This comparison is clearly simplistic (and the U.S. is large enough to influence inflation rates in other countries). But it is at least clear that a large part of recent inflation is not unique to the U.S (4).

The fact that inflation is temporarily elevated in many countries highlights the role that supply constraints may be playing. Delays in container shipping, for example, are increasing cost pressures. As one industry expert put it in the Journal of Commerce, a specialized shipping website:

… there is not a single root cause of these maladies. The situation is one of intertwined bottlenecks of port congestion, vessel shortages, equipment shortages, chassis shortages, rail shortages, and truck shortages. …

In essence, there is not a shortage when purely measuring the number of containers and ships available versus the amount of cargo in need of shipping. The problem is that it now takes much longer to move the cargo — and the equipment — which in turn soaks up large amounts of capacity.

And here policy makers need not be complacent. For example, they can help expand the number of truck drivers. Professor Yossi Sheffi, the director of the MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics, has pointed out that trucking delays exacerbate problems across the entire logistics system, and that a binding constraint on trucking capacity is the availability of drivers themselves. He suggests, among other steps, loosening federal regulations so that potential drivers are no longer disqualified solely because of previous marijuana use. The broader point is that many efforts could be made to address logistical chokepoints that are behind at least a significant part of the recent inflation spike.

The inflation debate will be further stoked on Thursday, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the May consumer price numbers. The Bloomberg survey of forecasters currently suggests the year-over-year headline number will be a CPI rise of 4.7 per cent, even higher than the April figure of 4.2 per cent, which will undoubtedly be seen as evidence in favor of the prosecution in the case of Summers v. Yellen. But it will take until much later in the year and perhaps well into 2022 to know for sure whether the superforecasters once again turn out to be right.

(1) It’s always risky to rely too heavily on macro-econometric models when one of the core drivers of the economy is mostly missing (as in a detailed model of the financial sector during the financial crisis of 2007-2008 and a detailed model of the pandemic now). So these forecasts should admittedly be taken with even more caution than normal.

(2) These inflation measures are for the personal consumption expenditure index, fourth quarter over fourth quarter.

(3) The current year-over-year inflation rates are contaminated by various price declines across countries at the beginning of the pandemic, so a good way to measure for this purpose is to examine inflation relative to the beginning of 2020, which is what the figure shows.

(4) Japan is a notable outlier in the other direction, with significant fiscal relief but still experiencing deflation (noteworthy in part because vaccination rates there remain quite low, even though they are now rising rapidly).